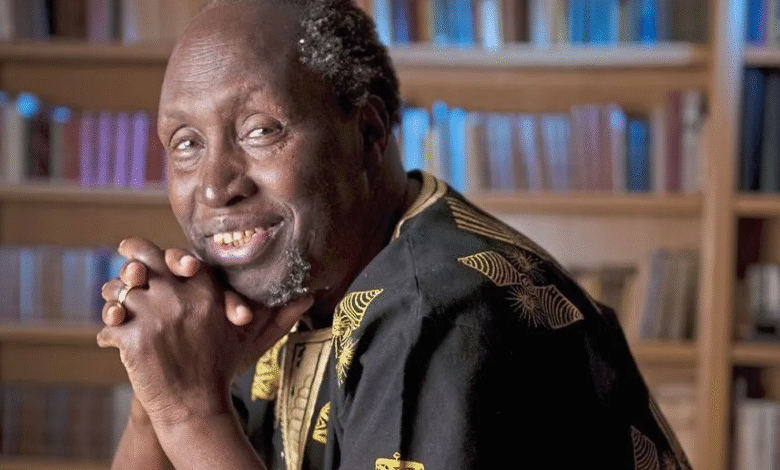

Ngugi wa Thiong’o, rebel pen and Pan-African conscience

Ngugi wa Thiong’o, who passed away on May 28, 2025, at the age of 87, leaves behind a monumental body of work, both literary and political. Novelist, playwright, essayist, and professor, he was one of the leading figures of African decolonial thought. From English to Kikuyu, from prison to exile, he never ceased to fight to “decolonise the mind.”

Born in 1938 in Kamiriithu, near Nairobi, under British rule, Ngugi wa Thiong’o was the child of a wounded world. He grew up in a peasant family caught in the tide of anti-colonial revolts and imperial violence. His pen emerged during adolescence as a cry for survival. He once said:

School tried to teach me that I was inferior. Books taught me that I was worthy

The heart of Africa beats in its language

From his very first novel, Weep Not, Child (1964), Ngugi revealed the inner turmoil of a people torn between two worlds: ancestral Africa and colonial oppression. But it was with Petals of Blood (1977) that he became an indispensable figure, fearlessly denouncing the betrayal of African elites after independence. The novel is a political firebrand, where the heroes of the people are crushed by corruption and injustice.

Colonialism robbed us of our land, neo-colonialism is robbing us of our dreams

A chained but free writer

In 1977, his Kikuyu-language play Ngaahika Ndeenda (“I Will Marry When I Want”) was performed in a community theatre. The audience applauded; the authorities panicked. Ngugi was arrested and detained without trial at the Kamiti Maximum Security Prison.

I had no pen, no paper. I wrote my novel on toilet paper

he later recalled about Devil on the Cross, his first novel written entirely in Kikuyu.

Released thanks to international mobilization, he went into exile, first in England, then in the United States, where he taught comparative literature. But he never cut himself off from Africa.

“Exile is a place, not an absence. I left Kenya, but Kenya never left me,”

he said in 2006 during a lecture in Nairobi.

Decolonising the mind, de-westernising thought

Ngugi wa Thiong’o was also a major thinker. In Decolonising the Mind (1986), he championed the use of African languages in the face of the linguistic domination of former colonial empires. For him, writing in Kikuyu was an act of liberation.

Language is a carrier of culture, a means of memory. If we are robbed of our language, we are robbed of our memory

This radical stance earned him both criticism and admiration. By rejecting English as his main language of creation, he restored dignity to African languages. His decision to never write in English again was, for him, a “linguistic divorce,” but above all, a marriage with his own truth.

Exile of the body, loyalty of the heart

Returning to Kenya in 2004 after more than twenty years in exile, he became the victim of a brutal attack. His wife was raped, and he was tortured. Traumatized, he returned to the United States. But he never stopped writing, bearing witness, or teaching. Secure the Base (2017) is a synthesis of his thought: liberation will not come from international aid, nor from copying foreign models, but from a recovered sense of self-worth, a celebrated culture, and a deeply rooted writing.

A missed Nobel, but an immortal legacy

Long considered a contender for the Nobel Prize in Literature, Ngugi wa Thiong’o never received it. Yet his books are studied around the world, and his ideas continue to inspire today’s intellectual struggles—from Nairobi to Dakar, from Paris to New York. His fight echoes those of Fanon, Cabral, and Césaire.

In 2022, Ngaahika Ndeenda was performed again in Nairobi, after 45 years of being banned. A full circle. A victory of art over censorship.

“They can imprison me, but not the words. Words, they fly over the walls,”

he said.

Ngugi wa Thiong’o is gone, but his words live on.

They continue to denounce, awaken, and heal. Because for him, writing was not a luxury—it was a necessity:

“The African writer must not decorate reality, he must transform it.”