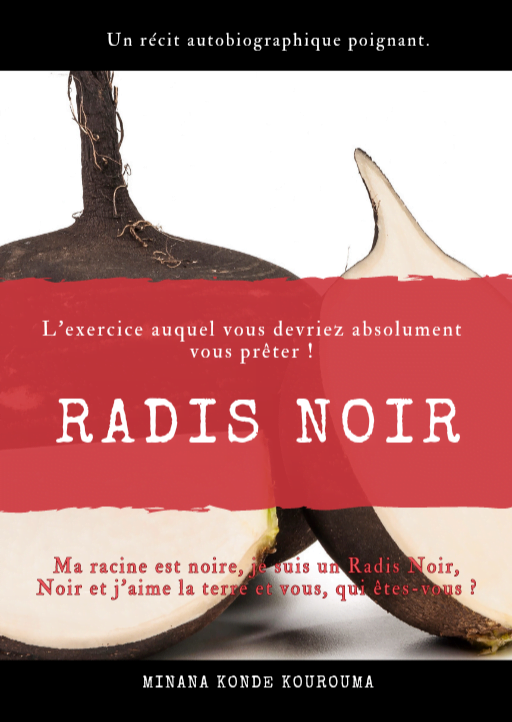

Culture / Books : Minana Kondé “Radis Noir will unfortunately always be topical, because there’s still a long way to go to eliminate discrimination and racism in France.”

“Radis Noir”, which has been in the news recently, is an essay by the French-Guinean writer Minana Kondé, known as Minako. The work, which has a strong autobiographical resonance, invites reflection on a number of Franco-African social issues.

By the editorial team

Could you introduce yourself to our readers?

I’m originally from Guinea. I grew up in France and studied law at the University of Lille, accounting at Cnam in Lille, international business management at EDHEC Business School in Lille and diplomacy and international relations at the Ecole de Politique Africaine in Nanterre. I grew up with my grandfather, a military officer, and my grandmother, a housewife. I had an African and, let’s say, partly European upbringing.

How did you get the idea for this book? What was your initial aim?

It was born out of a desire to address crucial issues facing our society today, particularly the African diaspora in France. My initial aim was to write an autobiographical pamphlet, but then I turned it into an exclusively autobiographical story, while keeping the same thread running through it.

Hence the format, a series of questions, literally, that you put to the reader on social issues such as racism, discrimination, Islam…?

In fact, I use a deliberately childish and original style in Radis Noir to invite readers to ask themselves questions. You might think that these are questions I’m asking myself. But they aren’t. They are questions I pose to readers to invite them to think about a variety of issues.

There are questions I’m not led to, but the reader is. So, it’s a book written with the intention of adapting to all readers, so that everyone can find their way around and ask themselves questions. Therefore, the questions don’t concern me directly. For example, if I say that maybe one day the tropics will be less tropical, could I live there, could I stand the extreme heat… (Sahara)… Personally, I’ve been used to Africa since I was a child, but that’s not the case for all Africans living in France. Not everyone has had the chance to get to know their homeland. And I stress the fundamental importance for everyone to know their origins.

To whom do you address these questions?

Questions that I address to everyone, to readers, to politicians, to racism, to Islamophobia… Questions that lead to reflection, to asking the right questions, to questioning oneself in order to discover and/or rediscover oneself through questioning and thinking differently. In this way, I invite readers to open up to themselves, to bring out the best in themselves.

Unfortunately, current events give your book a particular resonance: once again in France, the issue of discrimination is being raised with violence…

Indeed, and the last sentence of the first part of the book was « Madame Le Pen peigne, Monsieur Le hérisse Zemmour arrêtez-vous ou mariez-vous, ou plutôt chute la France va mal ».

Radis Noir is indeed a topical book, and one that will unfortunately always be topical, because discrimination and racism have come a long way in France and continue to flourish. Worse, racism is encouraged. That’s why the voices of the Fn-Rn and Reconquête continue to grow.

What can be done about it? Do we have to change everything?

The current French system completely excludes a section of the population who, despite having French nationality, are not recognized as French but as foreigners. It is true that nationality is only a document, and that is a hard fact of life.

The immigrant population and the descendants of immigrants are largely rejected. Only a few exceptions prove the rule.

The inhabitants of the neighborhoods and ‘zep’ zones rarely have the same level of education as other French people. They are likely to be excluded from the labor market, or forced to do odd jobs that don’t help them to prosper, or resort to selling drugs.

Can we castigate a population that we have excluded from society and locked up in housing estates?

The only short-term solutions are to overhaul the institution of the police, which is supposed to protect people, not kill them.

The only short-term solutions are to ban the use of racial profiling against targeted people.

The only short-term solutions are to review French arrest methods so that there are no more French George Floyds.

The only short-term solutions are to completely overhaul the way the French police work so that there are no more deaths.

The long-term solution is to open up France’s isolated cities. You can’t accuse a population of being communitarian if you put them in a common enclosure.

The long-term solutions are to provide a common national education system in the Zep areas, of the same quality as in the standard or upmarket areas. It has to be said that the level of education is not the same, the teachers are not the same and the courses offered are of lower quality.

We can’t blame a population for a lack of education if the education they’re supposed to get from school is of poor quality.

We can’t blame the parents, some of whom can’t read or write, for helping their children, but we can do something about it by giving them literacy classes and by giving the schools in the Zep zone the benefit of evening classes on the school timetable to raise their level and therefore their chances of getting out of the situation. Another long-term solution is to give them jobs. Studying is not enough to get by. They need quality training that is relevant to the labor market so that they can be fully integrated into society. And those who have the necessary level for higher education need to be helped to continue their studies through a system of financial support and guidance towards higher education with a clear exit. This system means that they can actually be employed once they have obtained their diplomas.