Cop 27:from climate frustration to radical implementation?

COP 27 is taking place against the backdrop of multiple and interacting crises, all competing for attention: food and energy insecurity, inflation, debt, Russia’s invasion of Ukraine and a looming recession. All this makes the climate summit in Sharm El-Sheikh (Egypt) the third ‘tough’ COP in a row, after COP 25 was moved from Chile to Madrid and a gap year when COP 26 in Glasgow was postponed due to the pandemic.

By Lara Lázaro Touza & Raul Alfaro-Pelico

COP 27 is taking place against the backdrop of multiple and interacting crises, all competing for attention: food and energy insecurity, inflation, debt, Russia’s invasion of Ukraine and a looming recession. All this makes the climate summit in Sharm El-Sheikh (Egypt) the third ‘tough’ COP in a row, after COP 25 was moved from Chile to Madrid and a gap year when COP 26 in Glasgow was postponed due to the pandemic.

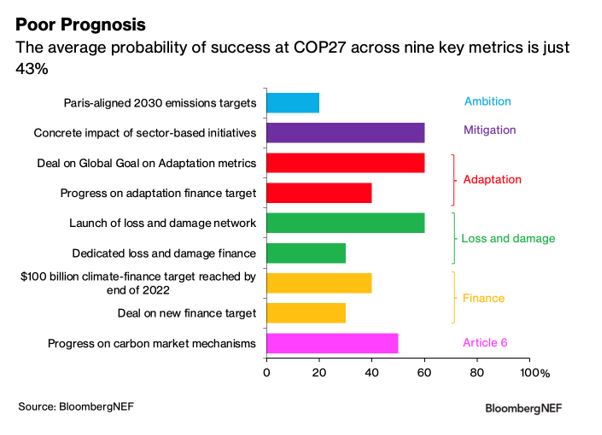

Unsurprisingly, the key topics to be addressed in Egypt, according to the new UNFCCC Executive secretary Simon Stiell, are enhancing mitigation ambition and furthering the Global Goal on Adaptation; addressing loss and damage; and financing climate action across these three areas. In addition, article 6 on market and non-market mechanisms needs to be further fleshed out to become fully operational. Preparatory work for the Global Stocktake in 2023 should also be in full swing at COP 27. The Egyptian presidency of this year’s COP announced after last year’s meeting that adaptation and finance would be its top COP priorities. This will be a departure from negotiations in previous years, which were largely focused on mitigation. However, current prospects for relative success in Egypt across the key issues being discussed are limited, creating additional pressure for this new African – and implementation-focused – COP to deliver.

Figure 1. Likelihood of ‘relative’ success at COP 27 across areas

Expectations based on previous COPs in Africa

To understand what we can expect from COP 27, it helps to take a look at what African COPs have delivered in the past. It was arguably ten summits ago, at COP 17 in Durban that the negotiations for the Paris Agreement began to gather momentum, building on the Copenhagen Accord and the Cancun Agreements. This was a significant undertaking that resulted in both developing and developed countries making voluntary climate commitments in Paris. Asymmetric historical responsibilities were reflected in the contributions of the Parties, despite insufficient action and solidarity from wealthy nations.

COP 18 in Doha resulted in the second commitment period (2012–2020) for the Kyoto Protocol, which covered just 15% of global greenhouse gas (GHG) emissions. The only consolation from Doha was the decision to institutionalise loss and damage through a mechanism that would be tailored to the most climate-vulnerable countries. Small Island Developing States had been fighting for this issue since 1992. International climate meetings are known to deliver slowly, and loss and damage (plus its finance) will be a key issue in Egypt. An agenda item on the matter has finally been included, alongside work building on the Glasgow Dialogue.

When negotiations returned to Africa after Doha, the Paris Agreement had entered into force. COP 22 in Marrakech kept conversations on adaptation alive. However, on mitigation, Trump’s election in November 2016 put the Paris Agreement and climate multilateralism in jeopardy.

COP 26: Taking stock of Glasgow

The Glasgow Climate Pact promised to bolster adaptation efforts, to accelerate GHG emission reductions and mobilise finance for both. At Sharm El-Sheikh, progress on the Global Goal on Adaptation will be sought, building on the Glasgow–Sharm El-Sheikh (GlaSS) Work Programme Discussions are also expected on the development of the adaptation goal and metrics to review progress towards said goal.

Climate ambition was underwhelming in Glasgow and pledges fell short of the commitments needed to limit temperature increases to 1.5°C. As of 26 October 2022, just 21 countries had updated their Nationally Determined Contributions (NDCs). Furthermore, the latest UNFCCC synthesis report on countries’ commitments found that GHG emissions will be 10.6% higher in 2030 than in 2010. At COP 27, preparatory work for the 2023 Global Stocktake will continue, with the goal of delivering a synthesis report in 2023 to inform the NDCs of countries in 2025. This should boost ambition.

On decarbonisation, while last minute deals were struck in Glasgow on ‘coal phase down’ and eliminating ‘inefficient’ fossil fuel subsidies, the IMF estimates that fossil fuel subsidies will rise from 6.8% of global GDP in 2020 (equivalent to $5.9 trillion) to 7.4% of global GDP in 2025. This trend will be driven by increased fossil fuel consumption in emerging markets.

As for annual international climate finance pledged by developed countries, OECD scenarios suggest the $100 billion goal could be achieved in 2023, three years later than agreed. The climate finance gap, which measures the shortfall between the $100 billion and finance that has actually been delivered, stood at $16.7 billion in 2020. This has undermined trust between developed and developing countries in the run up to COP 27.

Regarding loss and damage finance, some countries are starting to step up (eg, Denmark’s recent $13 million commitment, following the COP 26 pledges of Scotland and Belgium’s Wallonia region). Floods like the one suffered by Pakistan, where the bill will be in excess of $10 billion, have created a window of opportunity for more meaningful discussions on loss and damage finance in Egypt.

COP 26 managed to deliver the final elements of the Paris Rulebook. However, technical details on article 6 still need to be finalised during COP 27. These include reviews and reporting; transitioning activities under the Clean Development Mechanism (CDM) to article 6.4; the use of Certified Emission Reductions as part of meeting the Parties’ first NDCs; and developing a process for implementing the share of proceeds and ensuring the delivery of overall mitigation in global emissions.

Beyond rulebooks: chequebooks and implementation

In moving forward, the Global South awaits the effective implementation of emerging Just Energy Transition Partnerships. Developing countries also need to close the gaps between mitigation and science and between climate finance promised and delivered. Likewise, transformational adaptation is still pending. Top of mind at COP 27 will be increasing finance for adaptation and funding for loss and damage, while enabling easier access to all funds and grants. To deliver a net-zero world in a planet where people are already dealing with the consequences of ignoring red alerts from IPCC reports, action needs to shift from commitments to investment. This was highlighted by the Council of the European Union conclusions on climate finance and on COP 27.

But none of this will succeed if implementation (the theme of this year’s COP) through climate legislation and monitoring does not closely follow the Glasgow Climate Pact and the flurry of pledges made at COP 26. The EU, a long-standing directional climate leader, arguably offers one of the most comprehensive climate legislation packages. This includes the European Green Deal, the upcoming Fit for 55 package to implement it and its green response to COVID-19 via NextGenerationEU. Russia’s invasion of Ukraine and persistent shortages in global supply chains have also spurred the EU on to present its REPowerEU strategy for diversifying energy sources and suppliers. This includes a further push for renewables, albeit with some support for fossil fuel infrastructure – a move that has raised eyebrows in the climate community. Moreover, despite Germany backtracking on the Nord Stream gas deal, European climate credentials have been further called into question ahead of COP 27. The EU’s inclusion of nuclear power and gas in its sustainable finance taxonomy (albeit under strict conditions) risks emboldening others, as exemplified by South Korea’s decision to include gas in its taxonomy.

As regards implementation and the US, the tables have turned yet again. The new administration re-entered the Paris Agreement and passed the Inflation Reduction Act and the Infrastructure Investment and Jobs Act. The country is however failing to deliver on international climate finance; its mitigation gap will require enhanced ambition; and a Republican president in 2024 could lead to a third ‘made in America’ climate default (the first being the failure to ratify the Kyoto Protocol and the second the US withdrawal from the Paris Agreement). Moreover, and of material importance to COP 27, the US opposed a loss and damage facility at COP 26, highlighting its fear of having to face its liabilities. This is a sore point for developing countries, which will continue to push for loss and damage finance in Egypt. Furthermore, US–China climate relations are at a low after Nancy Pelosi’s visit to Taiwan. All this makes it hard to see how the Paris Agreement power couple might entice less enthusiastic Parties to step up their ambition in Egypt.

As we head to Egypt, COP 27 offers an opportunity to bridge the gap between NDCs and the actions needed to avert the worst impacts of a rapidly changing climate. For decades Africa and the Global South have defended their right to development, alongside the principle of common but differentiated responsibilities and consideration of respective capabilities in the light of national circumstances. Previous analyses of least developed countries, primarily in Africa and Small Island Developing States, found common ground on climate action, despite individual differences.

To move forward, it is essential to chart decarbonisation pathways and engage in partnerships. But collaboration must come with finance for adaptation and mitigation (eg, investments such the Africa Minigrids Programe) as well as with finance for loss and damage if the Global North is to rebuild trust. After the announcement at COP 26 of South Africa’s Just Energy Transition Partnership – an $8.5 billion package to transition out of coal – other African countries expect developed countries to foot the bill for decarbonisation. For instance, Nigeria’s Energy Transition Plan requires at least $10 billion per year to transition out of oil, with gas seen as a transition fuel until sufficient finance comes through. However, the Nigerian climate finance landscape means $17.7 billion a year is needed to deliver on the country’s NDC.

Extrapolating these needs across the continent, Africa will require $2.8 trillion this decade to deliver on all its climate pledges and position itself as a provider of climate solutions, not just a victim of climate change. In the meantime, 600 million Africans lack access to electricity, and 900 million lack access to clean cooking. With current annual climate finance flows to Africa at $30 billion, developed nations need to bring not just rulebooks but their chequebooks to Sharm El-Sheikh. COP 27 must see a drastic shift from insufficient pledges to radical implementation, with an African narrative highlighting the benefits of an energy transition that puts people first.

*Lara Lázaro is Senior Analyst at the Elcano Royal Institute and Lecturer in Economic Theory at Cardenal Cisneros University College in Madrid

Raul Alfaro-Pelico is the senior director of RMI’s Energy Transition Academy within the Global South Program.

Source : REAL INSTITUTO ELCANO