Close to Reopen? When Economic Autonomy Becomes a Necessity

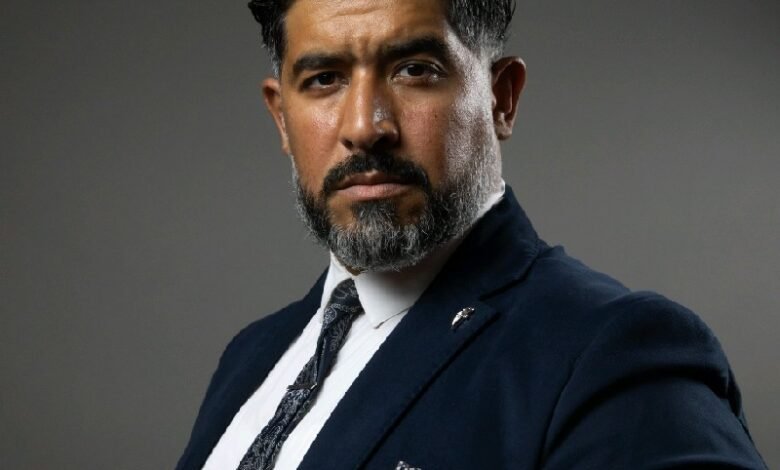

Cart’Afrik today publishes a column by Kaïs Mabrouk, PhD, researcher and expert in education and economics, who questions the dogma of free trade. Through examples from Russia to Algeria to South Korea, he argues that temporarily closing borders may be a necessary step to build true economic autonomy—before reopening with greater strength and resilience. By Kaïs Mabrouk*

The prevailing belief holds that open trade is always beneficial, that free trade is the only path to prosperity. Yet facts and history tell a different story. Ha-Joon Chang (South Korea), in Bad Samaritans: The Myth of Free Trade and the Secret History of Capitalism (2008), carefully dismantles this myth: today’s developed nations did not grow up in a bath of free trade. They thrived behind protective walls, long enough to build their industries. Only after consolidating their strength did they preach openness—while discouraging others from following the same path.

Harvard economist Dani Rodrik makes a similar point: a country seeking recovery must sometimes resist the temptation of immediate liberalization. Temporarily closing borders to certain imports can create the breathing space needed to reindustrialize, safeguard strategic sectors, and prevent the local market from becoming a mere outlet for foreign production. Reopening should then be gradual, selective, and guided by a clear national strategy.

The Volga

I had read these theses before. But yesterday, they took on a human face—that of Dimitri and Maria, two Russian academics vacationing in Hammamet. Opposed to all forms of violence, profoundly respectful of human life, and deeply internationalist, they told me how international sanctions, imposed after the war in Ukraine, reshaped their economic daily lives.

On their store shelves, French goods, Italian textiles, and German cars had disappeared. In their place: locally made products, at first less sophisticated, but quickly improving. Maria, always elegantly dressed and passionate about fashion, admitted: “I never imagined I could find joy and quality in clothes made in Russia. I always bought foreign brands. Today, I feel better dressed in our own textiles.” New factories opened, creating full employment. Agriculture, long neglected in favor of easier imports, was revived: farmers had to be “rearmed,” farms put back to work. Dimitri, smiling, confessed: “I had never tasted a Russian tomato. In St. Petersburg, our meals were always filled with imported produce.” The result: a revitalized productive fabric, a re-engaged workforce, and a less dependent economy.

The El Mordjene Effect

This example reminded me of conversations with my friend Nassim in Algeria. When Algiers drastically limited certain imports, he saw with his own eyes industries coming back to life—from food production to local processing. Yes, consumers had to adapt, accept that not everything would come from abroad. But the tangible benefits were clear: jobs, skills, resilience, and hidden gems (El Mordjene).

In Algeria too, the power of import regulation is being tested to revive local industry. In September 2023, the government created the High Council for Import Regulation to redirect funds toward national production and boost domestic industries. A few months later, in May 2024, the Minister of Commerce stressed that the goal was not to freeze imports but to rationalize them: in 2023, the import bill dropped from nearly USD 60 billion to USD 44 billion, favoring local transformation and job creation. This strategy was reaffirmed in June 2024 at the 55th Algiers International Fair, where the minister declared: “What we produce, we will not import,” citing wheat self-sufficiency, which alone saved USD 1.2 billion.

The Miracle of the Han River

South Korea, now hailed as a model of economic success, was not born in a free-trade utopia. Devastated by war in the 1950s, it rebuilt itself behind a wall of selective protectionism. The state, acting as a strategist, chose its industrial champions—the chaebols—shielded them from foreign giants until they grew strong enough to compete globally. Borders were ajar, but access to the domestic market was earned, aligned with national priorities. Only once its industrial backbone was solid did Seoul lower its shield, launching its ships, cars, and screens into world markets. The “Miracle of the Han River” was not the product of laissez-faire but of a state that knew how to close in order to open, to hold back in order to propel forward.

Wearing and Eating What We Produce

Some will argue this is not easy, that the “new free world” insists we buy from those who produce… for themselves. But perhaps the question should be reversed: how can we hope to rise again if we no longer produce anything at home?

Autonomy does not mean isolation. It is a strategic choice, sometimes imposed by circumstances, but one that can transform an economy. Closing the door is not shutting oneself off from the world—it is taking the time to learn to stand tall… and reopen from a position of strength.

And beyond all this, Carthage must be rebuilt.

*Kaïs Mabrouk, PhD, is a researcher in economics and specialist in educational policies. His work explores the intersection of development, economic sovereignty, and social dynamics across Africa and beyond.