By Nessan Akemakou*

Some, like UN Secretary-General Antonio Gutteres, speak of an « epidemic of coups d’état » in Africa. Is there a cure for unconstitutional power grabs? Over the past few decades, attempts have been made to prevent the scourge.

« Several measures by the international community have sought to prevent coups, leading to the creation of an « anti-coup norm ». A milestone for the African continent was the adoption of the Lomé Declaration by the African Union in 2000, which condemns any « unconstitutional change of government » and introduces several measures aimed at suspending states that violate this norm ».

These prophylactic ‘anti-coup’ treatments are clearly a failure. Every successful coup emboldens would-be coup plotters

In 2001, the Heads of State and Government of the Economic Community of West African States (ECOWAS) adopted the Protocol on Democracy and Good Governance. This instrument complements the Protocol on the Mechanism for Conflict Prevention, Management, Resolution, Peacekeeping and Security, adopted on December 10, 1999.

« A third option was to rely on a body of norms and laws, whether at the level of the African Union or regional institutions (ECOWAS, CEMAC, SADC, etc.), to prevent coups and deal with coup plotters. Several studies have shown that none of these concepts or norms has prevented a coup.

This is also the case in West Africa. The economic sanctions (freezing of assets, embargo) and political sanctions (suspension from the institution, recall of ambassadors) imposed by ECOWAS on the coup plotters in Mali, Burkina Faso and Guinea had more impact on the impoverished populations than on the new authorities. They did not prevent the new authorities from establishing themselves in the long term. In the case of Niger, in addition to the usual sanctions, ECOWAS is threatening armed intervention until power is returned to Mohamed Bazoum. This threat, which has not intimidated the military, seems far from being carried out, given the lack of support for it. And with good reason: the consequences for the region would be disastrous.

These prophylactic « anti-coup » treatments are clearly a failure. Every successful coup emboldens would-be coup plotters.

The panacea is utopian, but objectively there are levers that can be pulled to reduce the likelihood of coups. Priority should be given to fundamental reform of the state. The inadequacy of the post-colonial state is at the root of most of the ills that plague most coup-prone states.

We are proposing a state model that takes into account Africa’s endogenous and socio-cultural realities

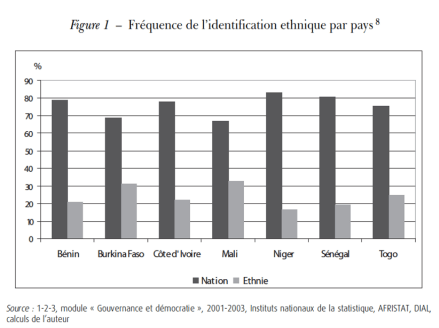

The failure of the post-colonial state in Africa can be explained in part by the application of an institutional model cast in the plaster of Western individualist rationality to communitarian social realities. Indeed, one of the defining features of African politics is ethnicity. The prevalence of ethnicity in Africa, despised and misunderstood, is seen as an obstacle to the emergence of the nation-state, which would be the alpha and omega of political modernity. The nation-state, on the other hand, is a historical phenomenon that emerged in eighteenth-century Western Europe after two or three centuries of incubation. For better or worse, colonization extended it to the whole world, but it did not emerge from the natural evolution of other cultures, and everything seems to contradict the idea of unilinear evolutionism, according to which these other societies would have had to go through it anyway. What’s more, logic dictates that this historical reality is not eternal, and since history is accelerating, it is doubtful whether it has a long future. It already seems incompatible with the state of the world and its problems.

Stubborn adherence to strict institutional mimicry can lead states that are ready for it (in rare cases where the graft has taken hold) straight into the current reefs that the European nation-state is running up against. Indeed, this state model is in crisis even in its original breeding ground, tending to capsize under the combined onslaught of globalization and waves of nationalist demands. The latter were relatively predictable, since « the systematic centralization of the state aims to destroy all horizontal solidarities, which are immediately defined as dangerous to national unity. In cultural terms, all minority or subjugated cultures are denied and doomed to destruction as soon as a systematic organization of education can be generalized, namely at the end of the 19th century ».

We propose a state model that takes into account Africa’s endogenous and socio-cultural realities. This, combined with improved political and economic conditions through a better distribution of resources, should reduce the risks of instability and, consequently, violent seizures of power.

The African state, as we understand it, is an inclusive state that does not set centralization as an absolute horizon. Indeed, it is common to confuse the ideal of political unity with the central and unitary nature of the state. But verticality and forced centralization tend to create symbolic and identity-based frustrations. Moreover, ethnic diversity is not synonymous with the absence or impossibility of unity. The affirmation of diversity is not the negation of unity. Homogeneity is not synonymous with unity, just as heterogeneity is not synonymous with discord.

It should be made clear from the outset that the following proposals do not claim to be a panacea, nor are they intended to apply to the diversity of African realities. Given the heterogeneity of Africa, the general model proposed must be adapted to local realities and the specific historical, political and social trajectories of each country.

A ‘return to the roots’ to inspire renewal of contemporary political systems in Africa

In the same way, we broadly advocate a « return to the roots » to inspire the renewal of contemporary political systems in Africa, but we must guard against an ingenuous re-enchantment with the past and not forget that traditional political practices in Africa are plural (…).

African states are in a process of consolidation and structuring, and like their peers, they will find their own way

In short, our main recommendation is that deep institutional reform, the adoption of the symbiotic state, a better distribution of political power, good governance and a fairer distribution of economic resources will significantly reduce or even eliminate the risk of coups d’état.

Coups d’état in Africa, tragic as they are, are not a historical anomaly but a ‘normal’ phenomenon in the process of consolidating ‘new’ political structures on the continent. The prevailing alarmism about authoritarian backsliding should not obscure the fact that, historically, most nations were formed in the turmoil of arms. It is often war that creates the state and the state that creates war, to use Charles Tilly’s phrase. The process of nation-building on every continent has been largely violent, and Africa is no exception. Europe has been marked by numerous wars and coups. African nations in the making are part of the course of world history. Gabon is unlikely to be the last country where the sound of boots on the ground will be followed by men in fatigues appearing on national television to announce the overthrow of the incumbent president.

We know from Hesiod that in the beginning there was chaos and that Zeus, triumphing over his father and the race of giants and titans, established himself as master and established order among gods and men. The coups in Africa give the impression of chaos. But order is at hand. Without lapsing into unwarranted historical determinism, it is fair to say that African states are in the process of consolidation and structuring and, like their peers, will find their own way that suits them.

*Nessan Akemakou is President of L’Afrique des Idées. He holds a PhD in political science and is a researcher at the Forum on Water Law and Governance at the University of Ottawa. His current work focuses on the blue economy and public policies for managing water resources in the African Union (AU) and Canada. He also teaches Foundations of African Politics at the University of Ottawa.