In New Delhi, IATA examines the challenges of African aviation

Gathered in New Delhi for the 81st Annual General Meeting of IATA (International Air Transport Association), global aviation leaders are assessing the state of the sector. While Africa shows dynamic passenger demand, it remains hampered by high costs, blocked funds and still too weak regional connectivity.

By Yousra Gouja, in New Delhi

It is in the Indian capital that the 81st Annual General Meeting of the International Air Transport Association (IATA) opens, hosted by IndiGo and in the presence of 1,700 industry players. More than four decades after the last Indian edition, the event marks a symbolic return to a country that has become an aviation giant. In this global context of transformation, attention turns to Africa, both a promise of growth and a mirror of its own roadblocks.

While global passenger demand is rising by 6% in 2025, Africa is doing better with +9%. Yet the continent still only accounts for 2 to 3% of global traffic

Between growing demand, emerging investments and persistent obstacles, the African continent is advancing… against the current.

While global passenger demand is rising by 6% in 2025, Africa is doing better with +9%. Yet the continent still only accounts for 2 to 3% of global traffic. The paradox is clear: a young population, rapid urbanization, continental integration underway… but an aviation sector that struggles to take off. Kamil Al-Awadhi, Regional Vice President for Africa and the Middle East at IATA, does not mince words: « If I had to start an airline today, it would certainly not be in Africa. The cost is too high. » The diagnosis is quantified: +17% on fuel, +12 to 15% on taxes, +10% on navigation fees, and up to +10% on maintenance and insurance. The cost of capital is also heavier. This accumulation significantly raises ticket prices, reducing accessibility for most of the population.

Connecting Africa to itself

Barely 20% of African air routes are intra-continental. This figure symbolizes a structural weakness: a fragmented sky, dominated by hubs outside the continent, which hampers regional mobility. “This is not a problem of open skies agreements. The real obstacle is the lack of political will and coordination,” says Kamil Al-Awadhi. The visa issue also remains a barrier. To date, only four countries – Benin, Rwanda, Gambia and Seychelles – welcome all Africans without a visa. Elsewhere, formalities remain discouraging. “Algeria suffers greatly from the current restrictions,” he laments. Yet, some positive signs are emerging.

If I had to start an airline today, it would certainly not be in Africa. The cost is too high

Ethiopia, supported by the African Development Bank (AfDB), is planning the construction of a new international airport. This mega project testifies to the country’s ambitions, already a leader in African aviation with Ethiopian Airlines. The same airline also co-manages the new Air Congo with the Democratic Republic of the Congo: an alliance where the DRC retains 51% of the capital, while the Ethiopian carrier provides operational expertise. This hybrid model shows that a strong African aviation sector can emerge without giving up national sovereignty.

Blocked funds strangling airlines

But this dynamic faces another structural issue: the non-repatriation of revenues. At the end of April 2025, 1.3 billion dollars belonging to airlines were blocked by governments, including 1.1 billion in Africa and the Middle East. Ten countries account for 80% of the total. Africa features prominently: Mozambique ($205M), Algeria ($178M), the XAF zone ($191M), Ethiopia ($44M). “This violates bilateral agreements. These practices discourage investment and weaken connectivity,” warns Willie Walsh, IATA’s Director General. Without access to their revenues, airlines cannot meet their foreign currency obligations or expand their network.

Ongoing efforts on safety… and ecology

In terms of safety, recent data offers a rare reason for satisfaction. The fatal accident rate in Africa dropped from 10.88 in 2022 to 6.38 in 2023, better than the five-year average of 7.11. But IATA wants to go further with CASIP, a joint initiative with ICAO, AFCAC, FAA, Boeing and others, to identify critical gaps and improve standards across the continent. “Promoting safety is fundamental. Having an accident is unfortunate. But not investigating is unforgivable,” stresses Kamil Al-Awadhi. For him, the problem is not only regulatory, it is also educational: “skills need to be strengthened. The lack of training hinders quality improvement.”

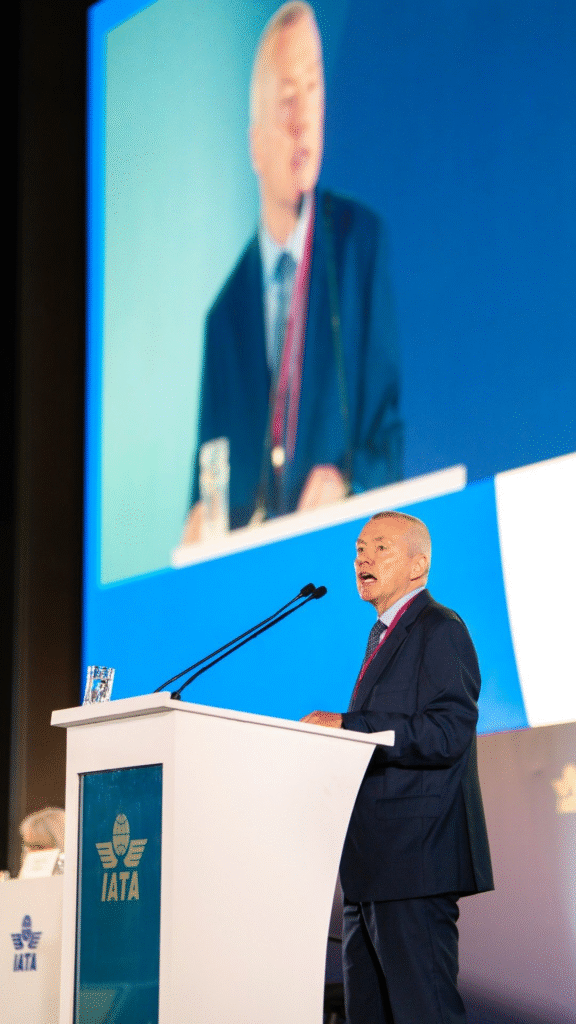

The aviation sector faces a major ecological challenge: achieving carbon neutrality by 2050 while continuing to grow. Globally, IATA estimates that without decarbonization measures, the sector’s emissions could reach 1,900 Mt of CO₂ in 2050. The key solution lies in the deployment of Sustainable Aviation Fuel (SAF), but these currently represent only about 0.7% of global consumption in 2025.

In Africa, where the aviation sector is booming, challenges are even more acute: low SAF accessibility, limited infrastructure, and dependence on international suppliers. The entry into force of the ReFuelEU legislation in January 2025 – requiring 2% SAF in fuels at European airports – has led some suppliers to pass the costs onto airlines, hampering the emergence of a transparent global SAF market. For Africa, this complicates access to sustainable solutions, despite strong potential in biomass and renewable energy.

345 million passengers by 2043

By 2043, Africa is expected to carry 345 million passengers, more than double 2023 levels. The potential is considerable. But political gridlocks, conflicts, international sanctions and economic tensions slow the emergence of a robust aviation ecosystem. “IATA can be a catalyst. But governments must understand that aviation is not a luxury. It is a development lever. The time is now,” concludes Kamil Al-Awadhi.