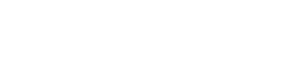

Ngũgĩ wa Thiong’o : « The colonial language is a cultural bomb »

In this excerpt from his seminal 1986 essay Decolonising the Mind, Kenyan writer Ngũgĩ wa Thiong’o explores language as a central weapon of colonialism. He denounces the symbolic violence of imposed European languages and calls for a revival of African languages to reclaim cultural and mental sovereignty.

By Ngũgĩ wa Thiong’o*

“The real aim of colonialism was to control the people’s wealth… But economic and political control can never be complete or effective without mental control. To control a people’s culture is to control their tools of self-definition in relationship to others.

For colonialism, this involved two aspects of the same process: the destruction or the deliberate undervaluing of a people’s culture, their art, dances, religions, history, geography, education, orature and literature, and the conscious elevation of the language of the coloniser.

The domination of a people’s language by the languages of the colonising nations was crucial to the domination of the mental universe of the colonised.

Language was the most important vehicle through which that power fascinated and held the soul prisoner. The bullet was the means of the physical subjugation. Language was the means of the spiritual subjugation.

When we spoke our languages, they were associated with low status, humiliation, corporal punishment, slow-footed intelligence and ability or downright stupidity, non-intelligibility and barbarism. This was reinforced by the world we met in the works of such geniuses of racism as a Rider Haggard or a Nicholas Monsarrat; not to mention the pronouncement of some of the giants of western intellectual and political establishment, such as Hume (« …The negro is naturally inferior to the whites… »), Thomas Jefferson (« …The blacks…are inferior to the whites on the endowments of both body and mind… »), or Hegel with his Africa comparable to a land of childhood, lying beyond the day of self-conscious history.

The effect of a cultural bomb is to annihilate a people’s belief in their names, in their languages, in their environment, in their heritage of struggle, in their unity, in their capacities and ultimately in themselves. It makes them see their past as one wasteland of non-achievement and it makes them want to distance themselves from that wasteland.

It makes them want to identify with that which is furthest removed from themselves; for instance, with other people’s languages rather than their own. It makes them identify with that which is decadent and reactionary, all those forces which would stop their own springs of life.

It even plants serious doubts about the moral rightness of struggle. Possibilities of triumph or victory are seen as remote, ridiculous dreams. The intended results are despair, despondency and a collective death-wish.

Thus, language and literature were taking us further and further from ourselves to other selves, from our world to other worlds.

What was being produced was a literature that was not really ours, a literature that was alienated from the majority of the people.

The question is this: we have inherited a language which we are now using. Is it possible to use it in such a way that we can express African realities? Can we use it to carry our own experiences? Or does it carry the weight of a colonial heritage that it cannot shake off?

My answer is that we can, but only if we see the language as a means of communication, not as a carrier of culture.

We must see the language as a tool, and not as a master.

We must see ourselves as the creators of language, not its victims.

We must reclaim our languages, our cultures, our histories, and our identities.

Only then can we truly decolonise our minds. »

*Ngũgĩ wa Thiong’o (1938–2025) was a world-renowned Kenyan writer and thinker who passed away on May 28, 2025, at the age of 87 in Buford, Georgia, USA. A towering figure in African literature, he was celebrated for his advocacy of cultural decolonization and the promotion of African languages. His body of work, including novels, essays, and plays, has had a profound impact on postcolonial thought.