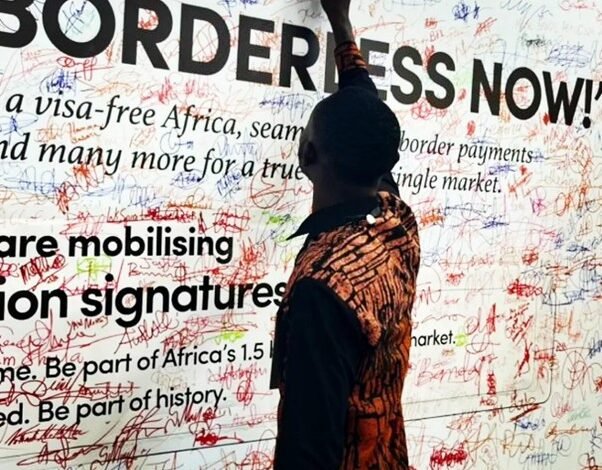

Building a Borderless Africa : an economic imperative, a lever for sovereignty

Gathered from February 4 to 6 in Accra for the Africa Prosperity Dialogues, public and private sector leaders renewed calls to accelerate continental integration. Behind the appeals to “Make Africa Borderless Now,” the stakes go far beyond political symbolism: building an integrated continental market capable of accelerating industrialization, boosting intra-African trade, and creating opportunities for the continent’s youth.

The primary argument is economic. Today, the continent still trades very little with itself. According to UNCTAD and the African Development Bank, intra-African trade fluctuates between 14% and 16% of total trade — far behind Europe, where it stands at around 60%, or Asia, above 50%. This fragmentation of markets limits economies of scale, slows industrial transformation, and increases production costs.

“Invisible” obstacles

For Wamkele Mene, Secretary-General of the AfCFTA, the continental trade agreement goes far beyond tariff issues alone: “The AfCFTA is not just a trade agreement; it is a development agreement.” Behind this statement lies the continent’s ability to transform its wealth locally. The World Bank estimates that its full implementation could generate up to $450 billion in additional income by 2035 and lift more than 30 million people out of extreme poverty.

Africa cannot trade if it cannot move its goods

Removing tariffs — set to be eliminated on 90% of tariff lines — will not be enough. The real obstacles are often invisible. Lengthy customs procedures, overlapping standards, administrative bottlenecks, and excessive logistics costs all hinder trade fluidity. In some landlocked countries, transport can account for up to 75% of the value of goods, according to the AfDB. Without efficient infrastructure, integration remains theoretical. As Afreximbank puts it: “Africa cannot trade if it cannot move its goods.”

Africa’s industrialization will not happen without market integration

The financial dimension is another major constraint. For a long time, more than 80% of intra-African payments were routed through correspondent banks outside the continent, generating costs and delays. The launch of the Pan-African Payment and Settlement System (PAPSS) aims precisely to enable transactions in local currencies. For Benedict Oramah, former President of Afreximbank, the challenge is strategic: “We must free African trade from the constraints of foreign currencies.”

Visa restrictions, non-recognition of diplomas, and fragmented labor markets

Integration must also serve industrialization. Producing for fragmented national markets of limited size discourages manufacturing investment. Conversely, an integrated continental market creates sufficient demand to make local processing viable. The UN Economic Commission for Africa estimates that the AfCFTA could increase intra-African exports of manufactured goods by more than 40%. Economist Carlos Lopes summarizes it clearly: “Africa’s industrialization will not happen without market integration.”

Beyond trade flows, free movement also concerns people. With more than 60% of its population under the age of 25, the continent holds the world’s largest demographic dividend. Yet visa restrictions, non-recognition of qualifications, and segmented labor markets continue to limit talent mobility, hampering innovation and entrepreneurship.

A tool of sovereignty

In an international context marked by health, climate, and geopolitical crises, integration is also emerging as a tool of sovereignty. Processing raw materials locally, securing regional supply chains, and reducing external dependence are becoming strategic priorities. As Moussa Faki Mahamat, Chairperson of the African Union Commission, emphasized: “The AfCFTA represents a historic opportunity to redefine Africa’s place in the global economy.”

Beyond economic mechanisms, building a borderless Africa is прежде всего a political and generational project. Former Chairperson of the African Union Commission, former South African minister, and a major figure of continental integration, Dr. Nkosazana Clarice Dlamini-Zuma embodies one of its strongest visions.

At the Africa Prosperity Dialogues in Accra, she delivered this call, which resonates as a compass for the continent’s future: “We must build an Africa where young people want to live, not where they want to leave.”

A borderless Africa, therefore, is not only about trade. It embodies the promise of a continent capable of offering its youth horizons that match its potential.